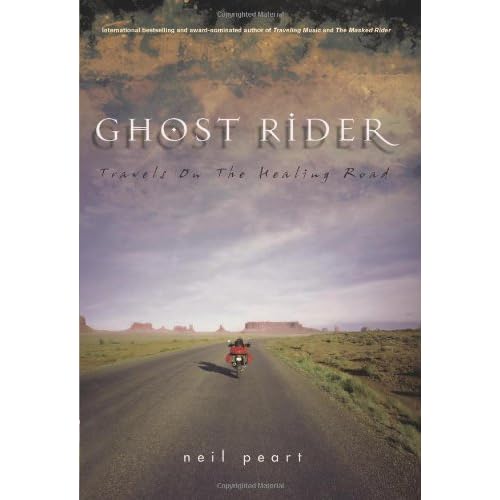

Book Review: "Ghost Rider" by Neil Peart

Posted: 16 July 2010 at 19:55:26

Well, I finished "Ghost Rider" by Neil Peart.

In retrospect, I'm not sure why it took me six years to finally get around to reading it. But, it did. Thom, one of my best friends, was reading "Ghost Rider" while we were traveling through Oregon and Washington many years back. He enjoyed Neil's commentary on Oregon's ridiculous laws that mandate that you do not pump your own gasoline. Instead, you must allow a minimum-wage worker to do it for you.

Thom and I share a common heritage of sorts. We both became hardcore fans of the band Rush when we were teenagers. Neil Peart is probably best known for being the amazing drummer for Rush. I venture to guess that a large proportion of the sales of "Ghost Rider" and Peart's three or four other books come from loyal Rush fans that can't find enough ways to support their favorite band.

I finally came around to ordering the book from Amazon after I attended a screening of the documentary "Rush: Beyond The Lighted Stage" when it was in limited theatrical release. There was a short segment in the documentary about Neil's hiatus from the music business, his motorcycle journeys across North America and down into Central America, and the resulting book he wrote about it. I decided it was time to finally read the dang thing.

Why would Neil Peart walk away from the successful role as drummer of one of the world's most successful rock bands? Well, it was a tragedy. Two tragedies, actually. First, his 19 year-old daughter, Neil's only child, died in a freak car accident on her way back to college from home. Then, his wife was diagnosed with cancer and died ten months after the car accident.

Neil was left with no family. Neil's wife Jackie took it especially hard when their daughter died. Neil had a rough time caring for Jackie as she grieved inconsoleably after their daughter's accident. Then, he had to deal with her descent and surrender to cancer.

Following his wife's death, Neil described himself as being nearly soulless, to the point of feeling like a ghost. He felt it was torture to sit around home where he had nothing but memories and things that reminded him of his wife and daughter. So, he mounted his "trusty steed," a BMW R1100GS motorcycle, and headed to The Yukon and Alaska, beginning a journey that attempted to heal a wounded heart, soothe a grieving soul, and patch a broken man.

For those not in the know, in addition to being the band's drummer, Neil has been the predominant lyricist for Rush since he joined the band in 1974. His influence on the band's music is heard not only in the complex rhythms and ever-shifting time signatures, but in the reflective and obviously literate lyrics.

Peart's book is littered with verses he wrote for various Rush songs that, more or less, fit that part of the book. I found it interesting, ironic perhaps, that for a man who seems obviously so inexperienced dealing with real human suffering, he sure had written anecdotally about it a lot over the years.

The writing is an unusual mix of straight-ahead storytelling mixed with copies of letters Neil wrote to friends and family along with transcribed excerpts from his personal journal writings. Sometimes, his letters also include journal excerpts.

Neil's letters went to different acquaintances, some closer to him than others, but most of the letters included in the book are correspondence sent by Neil to his friend, and riding partner, Brutus. Brutus was supposed to join Neil a month or so into the ride but got himself thrown in jail after being caught with a "'truckful' of a controlled substance of a leafy green nature."

While Neil doesn't come right out and acknowledge it, it does seem that he finds some rehabilitative help in writing... and writing... and writing... to Brutus. He tells Brutus everything he's doing, seeing, and thinking while he's on his road trip. Neil does this both to engage his own need for an outlet, but it also seems clear he wants to make things easier for his friend while he's in jail. I found that endearing and sweet. I've never had someone write to me that much, but then, I've never been in jail and I don't think any of my friends write anywhere close to as much as Neil Peart apparently does.

In addition to writing about his feelings as he's going through the motions of processing his unbearable grief, the highlights and notable sights of the country he's riding through, the hotels, motels, and lodges he stays at, the food he eats at the various restaurants and other dining facilities along the way, and the relative merits of BMW Motorcycle dealerships and service centers he deals with, Neil also provides a running list of the books and authors he's reading when he's not in the saddle.

As a result, I learned a lot about authors such as Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, Truman Copote, Jack Kerouac, Cormac McCarthy, Edward Abbey, and Hunter S. Thompson.

I think anybody who has been through any kind of significant suffering can empathize, to some extent, with what Neil describes having gone through in "Ghost Rider." I also think this book could be useful, therapeutically, for someone who is going through a difficult time dealing with some kind of loss.

I'm not in any way suggesting I "completely understand" how Neil Peart felt when he hopped on his motorcycle, hit the road, and repeatedly said he'd never return to playing the drums because he "wasn't that guy anymore." But, I do understand the desire to flee from your "old life," to run away on some mind-numbing distraction involving simply the road and nature.

I remember when I was young -- only 22-years-old -- I had been dumped, somewhat abruptly, by a girl that I thought the universe of. I had really thought I was going to spend the rest of my life with her and had grown quite attached to her company. It didn't help that I still had to see her around the college campus we both attended. I'm sure any of my friends at the time can attest, accompanied by sighs of recollection and plentiful amounts of eye-rolling, how grieved and confused I was; How I always wanted to ask the same questions (usually starting with the word "Why") over and over; How it didn't matter what the answers were, they never seemed to bring me any closer to moving on; How I neglected my schoolwork, participated in some self-destructive behavior, and spent quite a bit of time driving around on backroads through various rural and mountain areas listening to loud music.

Neil's detailed and carefully architected expositions about the landscapes he visits are amazing. The way he describes the deserts of the southwest, complete with flora and wildlife, precipitation cycles, and history makes it nearly effortless to imagine what he was describing. The same thing goes for the forests (and the high, barren areas) of the great north Canadian Yukon areas and Alaska, not to mention the cold, icy, muddy road conditions on the Dempster Highway to the Arctic Circle.

Neil employs the same degree of detail in describing the accommodations he finds at each lodging facility he stops at along the way. The same goes for the nearby restaurants.

In a nutshell, reading "Ghost Rider" kind of made me want to go out and buy a nice, big touring bike and hit the road visiting some of the wonders Neil describes.

The caveat, however, is that along with these picturesque word-paintings luring you to various destinations, Neil also injects the would-be traveler with a diatribe of hateful anti-tourist insults. It's like he's saying, "These are some amazing, wonderful places to visit, but all the people visiting them are ugly, fat, and stupid."

I think some that stems from the down mood he was in at the time.

One place he describes visiting that stood out for me was Telegraph Creek, a small settlement in the forests of the Yukon. Neil's description really gave me a vivid picture of it in my mind's eye.

The destination I had in mind was Telegraph Creek, because... well, because I liked the name. I first heard of it in Equinox ("The Magazine of Canadian Discovery," now defunct, unfortunately) in which the writer had pointed out that map-makers seemed to like Telegraph Creek because it gave them a name to put on an otherwise empty region, where northern British Columbia met the Alaskan Panhandle.

The settlement had flourished briefly twice, first during the Klondike gold rush when it was the head of navigation for steamboats carrying prospectors up the Stikine River. From there, they could travel overland to the Yukon goldfields on what came to be known as "The Bughouse Trail," its history replete with Jack London-style tales of starvation, scurvy, frostbite, and madness. The town's second life, and the source of its name, came from an American scheme to run a telegraph cable overland through Alaska, under the Bering Strait, and across Russia to connect with Europe, but shortly after the surveying was completed, the project was rendered pointless by the laying of the transatlantic cable. Telegraph Creek once again lapsed into a virtual ghost town, and the only present-day visitors seemed to be attracted by boat, raft, and kayaking expeditions on the Stikine River. Or by the name.

Another siren-call for me was the romantic lure of an isolated, storied destination which lay "at the end of the road." Telegraph Creek was a dot on the map at the end of a long unpaved road, far from anywhere, the kind of place Brutus and I used to dream about exploding (in fact, it was Brutus, in a recent telephone conversation, who had urged me go there). The guidebooks disagreed on whether I would have to navigate 74 miles or 74 kilometers of that road, but they agreed that it was "rough" and "often treacherous." In fact it turned out to be 112 kilometers (near enough 74 miles) of dirt and gravel winding through deep forest and steep switchbacks up and down the walls of "The Grand Canyon of the Stikine." In some places, the sheer cliffs of eroded, multi-layered rock did resemble a modest version of that famed stretch of the Colorado River, and sometime the road was a mere ledge perched on those vertical walls, dropping off into a frightening abyss.

My journal described it as a "scary, scary road," and I was fairly rattled when I pulled up in front of the Stikine Riverson café, general store, lodge, and boat-tour headquarters. All this was housed in one large white frame building facing the swift-moving river, and I learned later that it had been the original Hudson Bay Company trading post, situated just downriver, and had been moved piece by piece to Telegraph Creek. A few other abandoned-looking houses and a small church clustered on the river bank, but only the Riverson showed any signs of life.

The guidebooks said that a few rooms were available there, but if they happened to be filled it would be a long way back to any other lodgings. The cold, gloomy weather made the idea of camping uninviting, but once again I was glad to be carrying my little tent and sleeping bag, especially when the owner told me he was closing up for the weekend and taking the staff upriver in his tour boat to celebrate the end of their season. Then, after a moment's thought, he said that I was welcome to rent one of the rooms and stay there on my own. That was thoughtful, hospitable, and trusting of him, and I only asked what I might do for food. He told me there was a kitchen upstairs where I could prepare my own meals, so I bought a few provisions in the general store in the back of the building, including some fresh salmon from the river, and carried my bags to a small bedroom upstairs.

I watched through the café window as the owner and his three employees loaded their camping gear into the motor boat and my only regret was missing the opportunity for a tour of the river myself. I stood on the riverbank and watched the boat speed away upriver against the strong current, and felt a little excited, and a little fearful.

...

I slept soundly with my window open to the cool, fresh air and the murmuring of the river, and took a walk before breakfast on another chilly, overcast morning. Past ruined cabins and abandoned, moss-covered cars and pickups from the 1950s, a narrow path led up a high lava-rock cliff above a steep scree to an old graveyard overlooking the town. As I walked among the stones reading the inscriptions, the bare facts of names and dates had a whole new resonance for me, for I felt them as part of a story like mine, a story of love and loss. I thought about "Honey Joe," who had died at the age of 105 and was buried beside "Mrs. Joe," who he had outlived by about 40 years. Then there were all the babies, children, teenagers, and young men and women, and I found myself weeping for all the lost ones, theirs and mine. Ghost town indeed.

After I started reading "Ghost Rider," I told a friend that I had picked up the book. He said he remembered hearing or reading a little about it and that it struck him as being quite vain or that other reviews had painted Neil as being vain.

I don't think he's vain, I think he's just... odd. Neil Peart is better-read and better-schooled than probably 99% of people in the civilized world. He's likely afflicted with Aspergers Syndrome because it's clear he has serious social phobias and obsessive-compulsive tendencies. In his writing, he tends to be blunt, even if his prose is beautiful and intricate. He doesn't stop until he's faithfully described what he's thinking, what he's seen or what he's experienced. I can see how some people would find his writing style as vain, but I don't, really.

One personal observation I made to myself as I read this book was that Neil would have probably dealt much better with his tragic circumstances if he had not depleted himself of religion. Several times in the book he describes himself as a rational-scientific-skeptic. It made me think of a common religious perspective that an atheist is not someone who believes in nothing, but rather someone who can be persuaded to believe anything. There was a moment in the book where Neil takes a chance on a fortune teller who uses Tarot cards or similar to tell Neil exactly what's going in his life, leaving him stunned. It's no surprise that Neil has acquired a deck of the cards for himself before long.

But, yeah, it's sad to read Neil's constant bellyaching about how confused he is and how unfair his life has been to him and his family. Several times during the book I reflected on how fortunate I felt I was to have a belief system that give me a structure to sustain me if I were to go through such trying times.

Another surprising observation I had as I read the book was just how much of a liberal environmentalist Neil is. For someone who dedicated a record to Ayn Rand's "The Fountainhead," I guess I just thought he'd still have more of an Objectivist outlook toward nature, capitalism, and industry. I guess any of that he once had has been stolen away by his success and now he's, for a lack of a better description, a snobby left-winger who thinks we need to save the planet from ourselves.

Overall, I liked the book. I have some degree of interest in reading another Neil Peart book, but now I have so many other books on my reading lists thanks to what Neal said in this one.